Gender Divide: What’s the internet got to do with it?

Toxic male spaces that thrive on hating women are springing up; what does this mean for politics and women online? Plus a bonus story about a nonprofit tackling online harassment of girls through education.

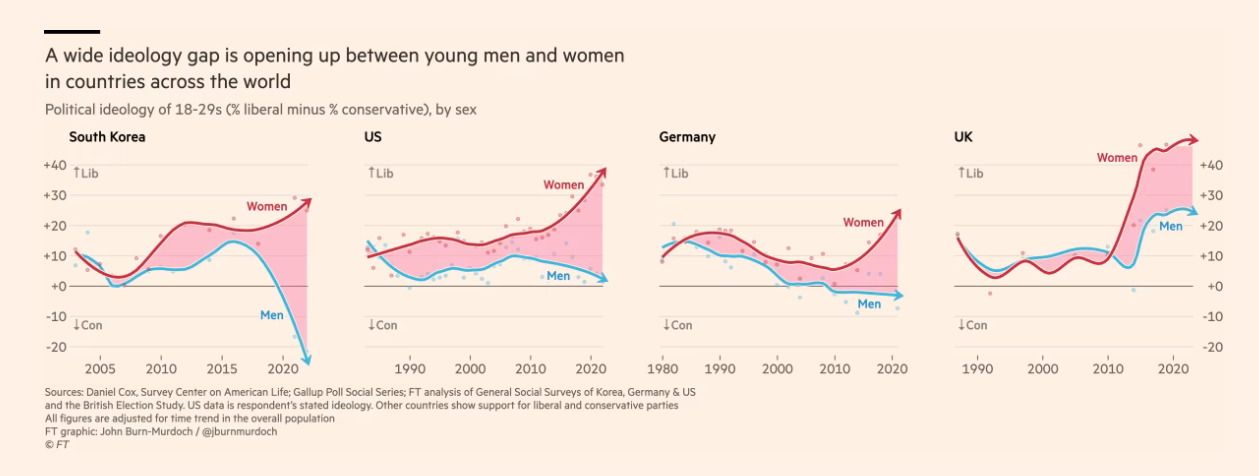

There is an emerging gender divide. From the US and UK to South Korea, young men and women are diverging in their political attitudes; with young men becoming more Conservative and women more Liberal.

According to YouGov, in the 2024 UK General elections, more young men than young women voted for the far-right Reform UK; 12% of 18-24 year old men versus 6% women in that age range.

This could be significant in political terms because it is starting to appear, at least anecdotally, that young men are being lured to ring-wing populist politics by so-called masculinity influencer gurus - including being influenced to vote for populists like Donald Trump.

In recent years, we have seen the springing up of more exclusive, toxic male spaces that thrive on hating women; what is known as the “manosphere”.

As Laura Bates explains, the manosphere, a disparate group of fairly insular communities, includes groups like “Men Going their Own Way”, who avoid all women because women are supposedly dangerous; to “men’s rights activists”, who go after feminists; to “incels”, the most violent, “‘involuntary celibates’, who believe women owe them sex and plot to rape and kill as many as possible”.

We don’t have to go into the depths of the internet to see what’s going on. There are male influencers a plenty on mainstream platforms like YouTube who have been monetising misogyny and growing the toxic masculinity cult; case in point, Andrew Tate.

Let’s zoom out a bit and look at the bigger picture of online harassment and misogyny. 85% of women on the internet* have been exposed to online violence. 38% have been direct victims, or 45% in the case of younger women (here, Generation Z and Millennials). That is almost every other girl or woman you know under the age of 43.

Of the women who personally experienced online violence, surveyed by The Economist’s Intelligence Unit in 2019, 32% “thought twice about posting again” and 30% “reduced [their] online presence”. So it’s no surprise that women participate less; with a 10-point gap between the percentage of men and women online — signalling a “digital gender divide”.

“Women and girls face unique online challenges; which are rooted in the patriarchal structures that fuel gender-based violence, limiting their participation online and offline and thus reducing their opportunities to access digital services and platforms,” says Amanda Manyame, Digital Rights Advisor at Equality Now, who has spent years studying tech-facilitated gender based violence.

So as we move towards the creation of more public squares online — albeit imperfect and not the utopia imagined in early Internet days — women and girls are unable to participate in these spaces fully because of harassment, stalking, doxxing, threats of physical violence, and image-based abuse among a whole list of other unfortunate occurrences.

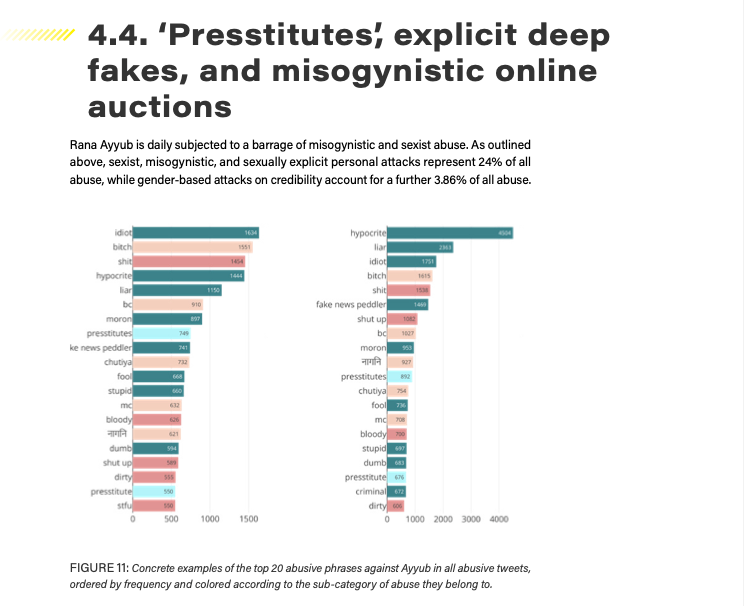

Right now, Rana Ayyub a prominent Indian journalist and fierce critic of the current Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing government - is in the eye of a violent misogynistic storm.

In 2022, the International Center For Journalists (ICFJ) said online attacks against Ayyub are an “internationally emblematic case of online violence”.

She is now at the receiving end of a new spate of attacks; she was doxxed online when a right-wing handle on X leaked her personal phone number, leading to a barrage of hateful messages and calls, and was targeted with sexually-explicit deepfakes of her being circulated online.

While public figures like Ayyub are major targets of malicious campaigns, online harassment remains a feature of life for women from all walks of life.

Talking about the difference in nature of attacks women face, Manyame says, “High-profile women face targeted attacks, amplified harm, and increased visibility. In contrast, general population women face more intimate attacks, less access to resources, and greater anonymity; making perpetrators harder to track.”

The digital divide does not stop here.

Pew Research Center this week reported that 30% of under 30s in the United States now get their news from influencers, and that two-thirds of these influencers are men. This is especially true for Facebook and YouTube.

So, what is actually up with the internet? We have got a male dominated sphere, accompanied by a male-driven content space (some of which specifically caters to pushing misogyny), peppered with dedicated female-hating forums. Our ‘alternative spaces’ are turning out to be alternative-to-women spaces; creating and reinforcing a digital divide.

And this is happening while young men are seemingly turning more Conservative; underlining a political gender divide. We need to better understand the relationship between the digital gender and political gender divide.

What can we do?

One nonprofit we spoke to, Commit2Change, thinks part of the answer might be in education.

Commit2Change, focuses on girls education and empowerment; working particularly with at-risk girls in India, Nepal and Bangladesh. Many of these girls were either orphaned or abandoned. Alongside support with traditional schooling, they make sure girls in their programme receive important life skills.

So when they started seeing incidents of online harassment spring up in their schools, they introduced a ‘digital citizenship and cyberbullying workshop’ to deal with the issues head on.

Speaking about the importance of the programme at this moment in time, Sumana Setty, Co-Founder of Commit2Change, says, "Anti-harassment training, and digital literacy more broadly, gives girls agency over their own lives. They don’t have to feel threatened or lesser than, and it gives them the confidence to stand tall and feel like they have a sense of control over their lives - which is something they haven’t been able to experience.”

Kuber Sharma, Executive Director, says when they first introduced a version of the workshop some years ago, the focus was “financial literacy” to equip girls to deal with digital fraud; which was becoming a growing issue as more people switched to digital payment platforms.

But then, he explains, they started noticing girls were also experiencing abuse on social media platforms like Instagram.

One of the first incidents was when a teenage girl in their programme faced serious trolling online for uploading a reel. It led to such shame that she refused to step out of the house and stopped going to school. Educators had to intervene to ensure she did not grow more isolated and went back to school.

In response their training involves introducing elements of digital education in bespoke workshops and normal curriculum, teaching practical steps to maintain security and privacy online, exercises on analysing “real-life incidents on cyberbullying and hacking”, and introduces pointers on how to "handle stress from social media" among other things.

This is just one step. Of course, more is needed to make an actual difference in the online life of women and girls. We need to have conversations with men and boys. We need governments to legislate better. We need platforms to change their business models. We need cultural interventions to shift attitudes.

Often these problems are so big we feel discouraged by not finding a singular simple solution to it. So this case study is just a way to say that change is often incremental, comes from different places and this is something crucial one nonprofit is doing. And that is not for nothing.