'The Walls Have Eyes’

In this Q&A, Manasa Narayanan speaks to Petra Molnar about the UK's push for unchecked AI ‘innovation’ and what it means for the existing surveillance state and migrants.

At the Paris AI Summit earlier this month, the UK and US refused to sign the “inclusive and sustainable” AI declaration. Perhaps Starmer felt it was important to appease Trump and US tech companies as trade deals are under negotiation. But it certainly is not good news given the trajectory AI ‘innovation’ has been taking; exacerbating racial and economic inequalities.

The Citizens investigation previously revealed how the Conservative government appeased Big Tech during the 2023 UK AI summit; how the summit and the AI taskforce lacked transparency and were entrenched in Big Tech interests. Our alternative summit spotlighted how the ‘doomist’ AI-will-end-humanity narrative adopted by the UK government at the time, glossed over some of the most pressing, real threats from Artificial Intelligence. Notably, AI-powered surveillance.

The UK has an extensive state surveillance system, and yet somehow it has managed to escape any scrutiny. The NSA leaks by Edward Snowden, implicating US state surveillance, also revealed how the GCHQ in the UK extensively and intrusively surveilled its citizens. In 2021, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the surveillance regime in place in the UK was “unlawful”. The judgement said,

The UK government’s interception of communications “did not contain sufficient ‘end-to-end’ safeguards to provide adequate and effective guarantees against arbitrariness and the risk of abuse.”

This means that anyone could be surveiled at any point in time, arbitrarily, whether one has engaged in any wrongdoing or not. Surveillance en masse.

Despite the ECHR ruling, the UK government went on to enhance their surveillance powers under The Investigatory Powers Act. Since then, use of digital surveillance in law enforcement and border control has only risen. It has become commonplace to have live facial recognition on UK streets. This despite Big Brother Watch finding that police deployment of live facial recognition is inaccurate 86% of time. Deployments since 2020 by Met Police resulted in the scanning of a whooping 157,566 faces, only to correctly identify eight people.

It’s the same piece of legislation that now allows the UK government to order Apple to pull its Advanced Data Protection. This means that UK Apple users will no longer be able to switch on end-end-encryption on cloud data and the government would be able to request this data from Apple. Previously, even Apple did not have access to this data.

In this context, I spoke to Petra Molnar, a lawyer and anthropologist, about her new book ‘The Walls Have Eyes: Surviving Migration In The Age Of Artificial Intelligence’ and what the unchecked push for AI ‘innovation’ and surveillance technology means for the UK and people on the move.

Petra is the co-creator of the Migration and Technology Monitor, a collective of journalists, academics, civil society organisations and filmmakers interrogating technological experiments on migrants. She is also the Associate Director of the Refugee Law Lab at York University and a Faculty Associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University.

Around 6-7 years ago, Petra was not thinking about technology at all. She was a practising refugee and immigration lawyer, working to reform the carceral system. But in 2017, with her colleague Lex Gill, a technology lawyer, she discovered that the Canadian government was using algorithmic decision-making to triage visa applications. They wrote a report about it that made its way into the government and contributed to the Treasury Board’s consultation towards a mandatory Algorithmic Impact Assessment tool. It was perhaps one of the first attempts to try and critique algorithmic decision-making used in migration systems from a human rights perspective. It opened her eyes to this whole intersection of issues between immigration, surveillance and technology.

Her book is the culmination of her experiences since then, including time she spent at the borders where surveillance tech is tested on some of the most vulnerable people.

Manasa: You have written a lot about digital surveillance, particularly surveillance used at the borders, in your book The Walls Have Eyes: Surviving Migration In The Age Of Artificial Intelligence. You take a very humane and holistic approach to show the impact of these technologies on the people on the move. What you find is that these technologies do not protect people and enhance ‘security’, but have the opposite effect. You write:

“Already violent global border policies are sharpened through the use of digital technologies… These technologies separate families, push people into life threatening terrains, and exacerbate the historical and systemic discrimination that is a daily reality for people on the move”.

Take us away from the technologies — the voiceprinting, fingerprinting, facial recognition, even AI-powered lie detectors that enable automatic detection of so-called ‘threats’, predictive analysis, somehow even ‘truth-telling’ — and explain what these technologies mean in practice for people attempting to cross borders? What is the human dimension of suffering that often gets missed in the narrative of ‘technological efficiency’?

Petra: Yeah, that's such great framing because ultimately in the conversations that we have around technology, it's so easy to get caught up in the projects and the draconian nature of it. But at the end of the day we always have to bring it back to the ecosystem in which it operates.

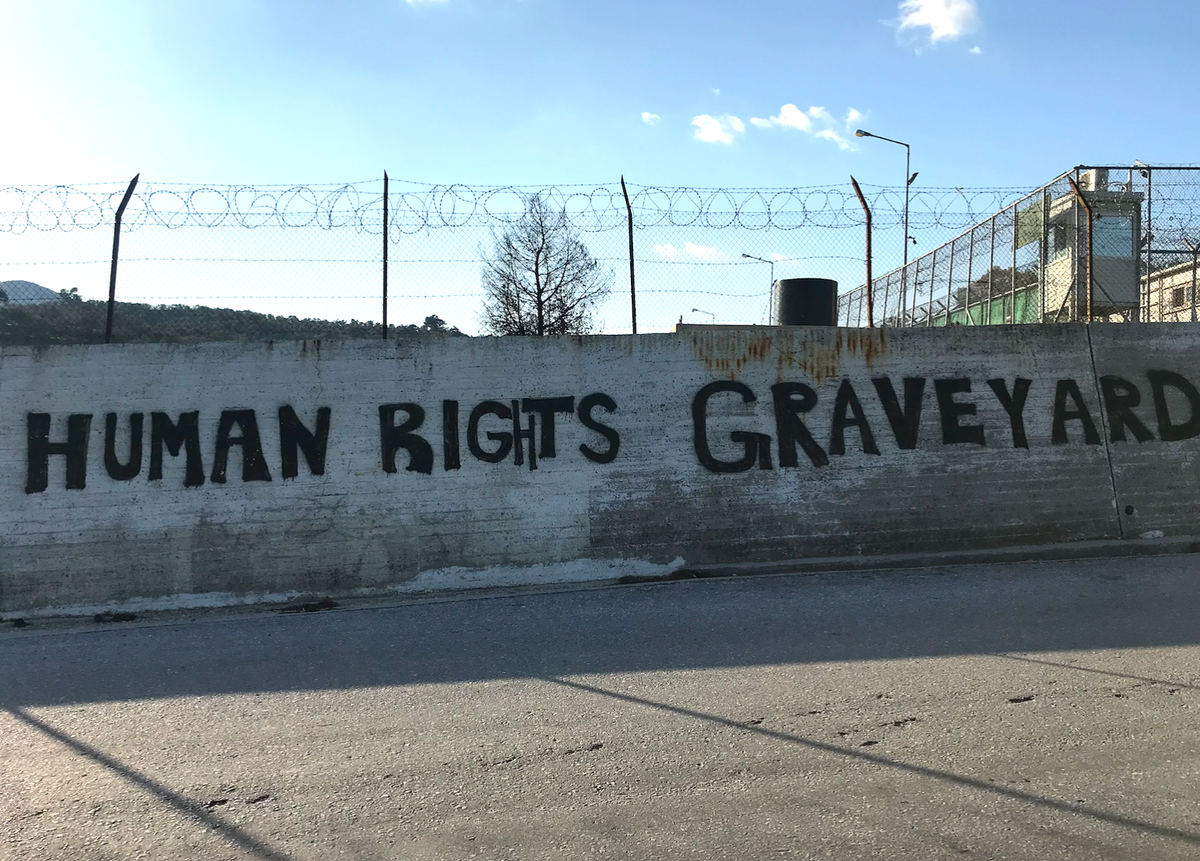

It is a violent ecosystem of exclusion that is predicated on racial logic, predicated on the politics of who deserves to live and die. It's predicated on painting entire communities as so-called ‘unwanted communities’ that are made to be trackable and intelligible and knowable. And we know that borders as a construct have been violent historically.

It's just that the technology is the latest manifestation of this historical violence and systemic discrimination that's inherent in the way that states police their sovereign territory. Now, there's also the element of the private sector playing into all of this. It really creates this ecosystem of human rights abuses that perhaps was always there. It's just that there's been a ratcheting up of it through the introduction of more technology, more surveillance, more data that we've been seeing in the last couple of decades.

Manasa: In terms of experiences of people on the border, what does that look like? Could you give some examples of the kind of technology that is deployed…

Petra: What helps me sometimes is to think about it temporally, almost as if we're following the journey of someone who's moving. Because there are so many different ways that technology can impact the way that a person is migrating now.

There's things that happen before you even move. So that can be things like having your social media scraped for the creation of a risk profile based on which mosque you go to on Fridays or who you associate with, that happens before you even leave your country.

Then things happen in either humanitarian response space, like refugee camps, or the border space in general. That's where we see the rise of biometric data. So using your body as a data point, whether it's iris scanning in Jordanian refugee camps that has been happening for many years now, or fingerprinting, or even your vein pattern.

And then at the border, that's where we see a lot of things like drones, cameras, but also more draconian projects like robodogs that were announced at the US-Mexico border a couple of years ago, predictive analytics that are used for border pushback operations.

And there's things that happen once you arrive at your intended destination like visa triaging algorithms, voice printing technology for identification, and carceral technologies. So technologies of detention and containment, things like wearable technology like ankle shackles or monitoring devices that are really becoming ubiquitous in the migration control space.

But really, pretty much at every single point of a person's journey, they're now interacting with some type of technology. Technology that's also largely unregulated and is very much a free for all in terms of how it's developed and deployed.

Manasa: You quote historian Sheila McManus who calls borders an “accumulation of terrible ideas”. There is much discussion we can have about the concept of borders itself, but AI-powered digital surveillance just seems to be an accumulation of terrible ideas - on speed.

Why do you think that this false narrative of AI-powered surveillance enabling secure borders and safe streets persist?

Petra: I think it has a lot to do with how technology is thought of globally as this force for innovation and economic development and countries wanting to be part of that conversation. Some colleagues call it the AI arms race. And we really see this playing out geopolitically a lot. In terms of, for example, how the UK positions itself as an AI leader, right? Canada does the same. The US as well. China too.

There's this kind of jostling for power when it comes to the AI space, because that's the kind of hot space, even though we know that actually a lot of AI technology doesn't even work or it creates so many other issues in terms of bias, discrimination, even efficiency. But that almost doesn't seem to matter because that is the sexy tech in vogue.

That then plays into one of the animating issues of our time being migration and migration control. So it creates this kind of ‘perfect marriage’ of two dynamic ideas that are deeply flawed and somehow then they kind of co-mingle in this way that actually ends up hurting a lot of people.

Manasa: This month, we saw UK PM Keir Starmer refuse to sign the “inclusive and sustainable” AI agreement. Their “AI opportunities Action Plan”, that they set out at the start of this year, just seems like a manic ill-considered push for more AI spending, development and incorporation in the public and private sectors. They have not ruled out the use of sensitive health records like NHS data. There is a blind move to rapidly embed AI in public sectors, like schools, hospitals, and transport. There are plans to change copyright laws so a lot of valuable knowledge can become fair game for AI companies.

Should we worry that this sort of unchecked AI ‘innovation’ approach would only further worsen the surveillance state we already have?

Petra: Yeah, absolutely. It's a really worrisome moment because innovation seems to have been tied with corporate capture and profit-making in the border space. Theorists and journalists like Todd Miller have been calling it the border industrial complex, but ultimately it's the surveillance industrial complex.

The fact that there's so much money to be made in innovating in this space, whether it's a public-private partnership or private sector by itself. It seems like there's so many actors now jostling for influence and power in order to make money. And this is why we see that a lot of governance and regulation is weak, like the EU AI Act, which was ratified last year, which I think was such a massive missed opportunity when it comes to actually creating a governance document that could have set some guardrails around some of the more high-risk implementations of AI. Surprise, surprise on the border tech file, it does not go nearly far enough in terms of creating any kind of safeguards. Let alone a moratorium or a ban on things like predictive analytics or anything like that.

But then you have some of these softer mechanisms like you mentioned, the AI “inclusive and sustainable” declaration. I mean, we've seen a lot of these pronouncements and statements and declarations. Maybe this will sound strange coming from someone who actually practices international human rights law, which is also not enforceable. And these soft approaches are important from a normative sense because they do set a precedent and a standard of how we think about things, but at the end of the day they're not enforceable. And then you have major geopolitical actors like the UK and the US not even bothering to sign on, right? So what does that then do to the kind of scope of this declaration or these pronouncements?

I can't say I'm surprised that the UK and the US didn't sign it, perhaps there's a worry that this would alienate private sector partners. I don't know if I can say the same about the UK just yet. But if we look at the US situation, the Oval Office has essentially been opened to private sector interests. Especially now during the second Trump presidency, but even before that.

So there is that relationship between the private sector's interests in making money and doing as little as possible to govern and regulate AI. Because there is this foundational understanding or idea that animates everything, that somehow governance stifles innovation. But you know what? Maybe some innovation needs to be stifled.

Maybe those are the kind of conversations that we need to be having. These are not very acceptable conversations for the governments around the world.

Manasa: Just taking a step back though, for someone new to this subject, could you explain where Artificial Intelligence comes into all of this? How does AI get incorporated in digital surveillance and turbocharge existing surveillance?

And another dimension to that, for anyone who says borders and surveillance have existed before the entry of digital technologies. What is new and worrying now?

Petra: The AI moment is an important one because there's definitely been a bit of an intensification of what's already been happening at the border. I mean, to try and explain AI can be a bit daunting because it's such a major class of technologies and projects.

But I take a really broad definition in my work. It's essentially anything that can automate or replace a human decision-maker in the life cycle of a project. So that can be an algorithm that uses big datasets to make predictions. It can be any kind of natural language processing project. It can also be machine learning. But essentially it is a way to animate decisions that would otherwise be made by human beings, at least in the immigration space.

And to give a granular example, we see artificial intelligence being introduced into things like surveillance at the border. So at the US-Mexico corridor, for example, there are Israeli surveillance towers by a company called Elbit Systems, which has been pioneering the use of artificial intelligence for surveillance purposes, first in Palestine and then exported out into the US space and the EU space. And essentially these towers use artificial intelligence to create a surveillance dragnet over the Arizona desert. So they're able to autonomously scan huge swaths of the land, try and make predictions about what likely constitutes movement, whether that needs to be flagged to border enforcement. Drones also are unpiloted. They can make autonomous decisions about what to surveil, where to go. And there are other types of surveillance at the border that also use AI.

Manasa: Do you think that we should worry more because of that?

Petra: I do think so. For a variety of reasons, one being, the kind of governance and regulation conversation. The fact that we don't have a lot of laws to put guardrails around the development of AI and then not only that, but its development in these high-risk spaces; whether that's border control, criminal justice and predictive policing, or any kind of biometric mass surveillance that uses AI in public spaces.

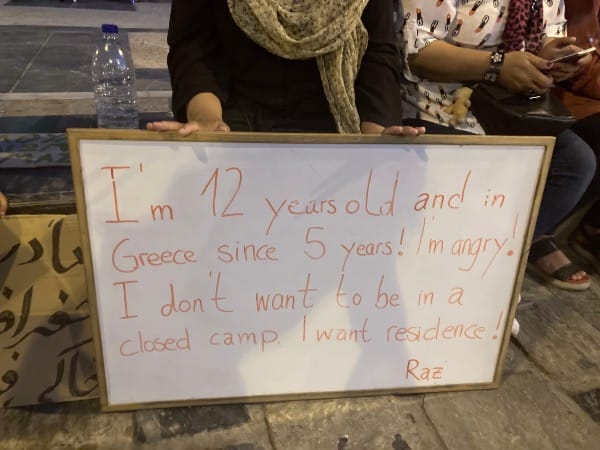

So there's the human rights concerns and the governance concerns. And I don't want to get too philosophical, but I think the other set of concerns is actually like, what does this then do to the human to human relationship once we start automating either partially or fully these decisions that are already very complex. Especially when you look at the border. So many people have had very difficult experiences at the airport or trying to enter a country because of the discretionary nature of immigration decision-making. It often hinges on one officer and how they're feeling that day. Seemingly that's what it seems like. And what kind of biases and discriminatory frameworks can it put on you as you're crossing. We know that that's already happening in the border system.

So then what happens when you start automating or replacing humans who are already imperfect with machine learning or AI? The concern is that there's a bit of what's called responsibility laundering, essentially being able to say, well, the technology told me to. Or automation bias, assuming that something that's rendered by an automatic tool is somehow more truthful or objective than if the same decision was made by a human.

And again, at least in the border space, it's already such an opaque and discretionary space, you can have two officers look at the exact same set of evidence and render two completely different yet equally legally valid determinations. So if we know that there's so much discretion, what then does AI add to that? What does it obscure? And again, what does that do to our ability to hold powerful actors to account?

If AI then also creates this kind of smokescreen between you as the rights holder, oftentimes the rights holder that already belongs to a marginalised community, and then powerful actors who are able to hide behind the technology that's increasingly automating these already opaque decisions.

Manasa: After the NSA leaks by whistleblower Edward Snowden, the United States at least had some reckoning with mass state surveillance. Even now we see reporting around border technologies, like your work on digital surveillance at the US-Mexico border.

Not to say that has dampened surveillance efforts. But the UK has not even received that level of basic scrutiny. There still exists this narrative that only undemocratic or dictatorial states like China, Iran and North Korea employ large scale surveillance and oppressive technologies. Why do you think that is?

Petra: Well, it's a really powerful framing that I think Western states in particular are able to employ. Canada does the same. Like in Canada, we kind of learn from you guys and sometimes vice-versa about just how to frame the conversation around who is the kind of actor that has to be policed when it comes to tech. And usually it's China, right? Rather than looking at Israel or the United States or the UK or the EU or Canada. Although Canada again, pretty minor player. I think it's not an accident. Because again, it obfuscates the kind of geopolitics that are actually the ones that are driving what we innovate on and why.

And it's important to have broader geopolitical perspectives on this too because so much of the tech doesn't just stay in the one location where it's developed. Even though the UK in particular wants to present itself as a democratic country and a rights-upholding nation, it purchases a lot of technology from actors that are not that. So then what does that do to its human rights record? Same with Canada, same with the United States. I think it's kind of presenting a facade of being both an AI leader and also being a human rights first country. But oftentimes you can't really have both. I think a lot of Western nations like to keep that image, which of course, as soon as you lift the lid, you realise it's not like that at all.

Manasa: You touch upon the importance of storytelling at the very beginning of the book. One of the biggest challenges in front of progressives now is how to better tell the immigration story. Because even if misleading or false, you would see people floating these right-wing talking points about jobs and crime.

Even when you have facts on your side as a pro-immigration activist, how do you speak to a contrarian? Do you think we need to get better at that?

Petra: Yeah, definitely. I faced that kind of reckoning myself in my own work many times where you feel so frustrated because when you are armed with facts and figures and even the economic side of migration. The fact that it is actually a benefit to Western nations, like the UK and Canada. You're met with right-wing rhetoric that is very powerful and it somehow sticks better in people's minds because it activates for people who are living through intersecting crises, the cost of living, post-Covid, all of these things that people are contending with. I think it's easy to blame a scapegoat. And the scapegoats in vogue are people on the move.

Storytelling can be helpful here. In my experience, it has been because even in the most heated conversation you can disagree on analysis and apparently in the post-truth era, even on facts. But it is harder to disagree with a human story. And I think we as a sector need to do a better job of humanising what it is that we're talking about and what these technologies of surveillance and control and coercion are really doing to real people and real communities.

And that's not just from a methodology perspective, although I think it is for researchers and lawyers or journalists to really think about what kind of storytelling and narratives we're putting out there. But I think it goes deeper than that.

It's actually also a conversation about who counts as an expert and who is actually able to talk to these kinds of issues. Like where are all the people on the move currently? Why are they not part of the conversation and why are they not seen as experts? I think those kinds of reframing around the production of knowledge in this space play into it too.

The conversation was slightly edited for clarity and brevity.