When the few control what the many see

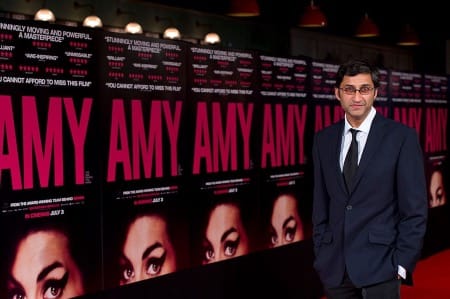

Director Asif Kapadia on the challenges of getting 2073 made and released.

Academy Award and BAFTA-winning director Asif Kapadia in conversation with our journalist Manasa Narayanan, discussing his new feature documentary 2073.

In part one of this conversation, published yesterday, Asif spoke about what motivated him to make this film. In part two, he talks about the difficulties of making and releasing this film, and how he has found hope through the screenings.

Over the last months we’ve been working closely with Asif, because the issues his film 2073 brings to life are the same ones we have campaigned about for years; the cosy relationship between our world leaders and the Tech Bros, their unchecked wealth and power, the increasing use of surveillance technology, the decimation of our information space, and more.

If you've not caught this brilliant film yet, we are holding a special screening with our friends at Byline Times. Head over to the link below to find out more and get tickets.

Manasa: Let's talk about the stage where you have made the film and have the colossal task of getting people to watch it. Would you say it was more challenging with 2073, trying to get, for example, streamers to be interested, in comparison to other films you've made?

Asif: They are all hard. Anyone who has ever made a film, it is a miracle any film gets made. It is really hard making documentaries and it is really hard making a documentary like this which is not about a famous person. And so it was a challenge to do something like this.

It was very difficult to get it financed. For various reasons. The whole world was affected by Covid. And this film started during Covid. People were not going out. Nobody knew if cinema was even going to come back because the streamers had stepped in. People were just sitting at home getting everything delivered to them, not just food, but including what they watched. And so the way that works is we're told there are certain things that people want to watch and not want to watch.

But the reality for a lot of streamers is they do not want to piss off world leaders. Because if you piss certain world leaders, they might not show your films or they might not show your service.

And that's actually what the film is about. If we have a few tech companies that decide what gets made, what gets seen, what gets shown, what journalists can say, that is not healthy. That is where we have ended up. And it is going to go further and further that way if people who are all from a certain social group, age, class, wealth, colour, sexuality, control everything.

So my film is a little microcosm of that because, one, people say, people want to be cheered up as they are just coming out of Covid. And I was like, yeah but I still think people want to know what the fuck is going on. And, secondly, it is not a simple biopic because it is not about one person.

Also, I am pitching this before I made it, no one knows what the hell the film is going to be like. And then by the time the film comes out, people are really not wanting to piss off certain very powerful people.

Some people might not like the film, which is fine. But what I found is, in a way, the spirit of the film is independent. And actually it being shown at the cinema… everyone wants a big hit. Everyone would love a film to get great reviews, win loads of awards, make lots of money. I have been very lucky that has happened with my previous projects. I have been there. But I also know the spirit of this film is anti-establishment. It is kind of fighting the system. It is about characters who are literally living underground. So it's almost like it couldn't be any other way.

Manasa: We will come to the bit about people wanting cheer later on, but I have heard you speak many times about the role of a filmmaker and how it is to tell stories and what people do with it is kind of up to them. But there is this friend of yours and someone you featured in this film, Maria Ressa, the Nobel laureate, who says that we are all activists now. Has the making of the film in any way changed or has it reinforced your view about your role as a filmmaker?

Asif: I mean, I have always been like this. It is just that this project is more explicitly political in a way, and more explicitly about journalism because the film comes out of the times we are living in and speaks to that.

So it is kind of hard to explain. Making a movie, for me, because I take quite a long time making a movie, is the equivalent of someone deciding to write a novel. Or doing a PhD. You are going to spend four or five years of your life on something, you might as well do it on something you care about. And what I cared about coming out of Covid was trying to understand the world because I was of a certain age, because I had kids of a certain age. Because I am the grown-up now in my house. There would have been a time when all I wanted to do was make a film about a footballer or make a film about a musician. And that was fine. But the person who did those films was a different person, a different age, and the world was different.

So for me, growing up in Hackney, with my family, my sisters, father and mother, we were quite political. We did read newspapers. I cared about what was going on in the world because of my experience and my background. I am one of those people that is surveilled. I am one of those people that is watched when I go to the airport. I am one of those people when younger that gets stopped by the police because, you know, 'do you really own that car?' That was just normal for a lot of us. So this experience is not something I have suddenly understood that the world is a certain way. It has always been like this. This is just a film which is explicitly about that, because I thought it was an important one and the one that I needed to make and wanted to make. And there are lots of easier films that I could have done.

And actually, what it was, having made films about singers, footballers, racing drivers and musicians, or ballet films, this one was like, who do I think are the most important people? And the most important people to me are Maria Ressa, Carole Cadwalladr and Rana Ayyub and other brilliant journalists around the world who did not all make the cut but who I interviewed. I was like, the world really needs good journalists right now, and my job as a filmmaker is to speak to them. And I want film audiences to know who they are, because certain people who read certain newspapers or live in certain countries might know them. But not everyone does. And that was the other challenge that a lot of financiers said, well, everyone knows all this. And I am like, who, where? And also, if you know all this, what did you do about it?

And my intention was to try to connect the dots between lots of different issues and lots of different people and lots of different countries, which I had not really seen before.

I do not think you can just be a climate activist and worry about the UK if you do not understand America, and you cannot deal with tech if you do not understand surveillance, or you cannot worry about surveillance if you do not understand power and money and who is getting elected and how they are using WhatsApp or how they use Facebook. And Facebook is just as important if you care about, you know, freedom and rights and protests. And so I just thought it was all the same thing.

Manasa: For people reading, I should say, spoiler alert! I've seen the film, twice actually now. And the film does not end on a very hopeful note. And in the screenings, I have heard you talk about how that was a conscious decision to not have a hopeful ending. Would you talk a bit about that? And now that you have done a few screenings and you have had feedback from your audiences directly, have you found any hope that you did not have while you were making the film?

Asif: Yeah, the ending of the film is truthful to how I felt. I think a lot of it is about what am I trying to say, and what I want the audience to feel. And the screenings that we have had... the audience is really hit by it. And so therefore, if someone had said, give me some more hope and I had put it in, I think it would look really fake, considering what is going on in the film or in the world right now.

Because it was like, actually, this is more truthful, this is more honest of the initial feeling I had of why I wanted to make a film. But also the world we are in, where people are worried about what is going to happen. Is there going to be revenge? Are these leaders in power going to come for everyone because of something they wrote or did in the past?

So in terms of what is the hope? The hope I have found when screening the film is every single time we have shown it, the Q&As have been amazing. No matter where, which country, wherever we have shown it, the audience wants to talk. And I still feel like a lot of people are at stage one.

Stage one is, you're not crazy. The fact that you are seeing and experiencing this or you’re worried about what is going on in the world is fine, because I know I was. And that is why I wanted to make the film. The number of people in the audience, wherever I have been, who have said, you have basically expressed what I have been trying to put together and connected it up in a way that I could not really say, including people like Carole, Maria and Rana. Because if you work in literature or if you are a writer or a journalist, there is a certain way you can express yourself. And people who read that newspaper, read your articles or follow you on social media, will get it right?

The thing about cinema is it works in a different way. It is emotional in a different way. And the reason I wanted to make it a sci fi-film, it is a movie. They may never have heard of Rana, but then they will hear her. And I am hoping they go, 'she was amazing. I would like to know more about her.' And Maria and Carole. They are the hope.

So number one is: people will go and want to know more. The screenings have meant people have started connecting because when I started the film I got to know a lot of different groups. Over here there was a group that was worried about the climate. Then over here are the people who are worried about politics and the breakdown of democracy or about voting systems. And then there are people over here that are anti-establishment. And it was all these different groups that I met and none of them seemed to be mixing. And what was really great was like we would just have a screening and there would be groups from different interests and different countries and different languages who would be in a room who would just start talking to each other and sharing contact details and realising, your struggle is my struggle.

Something happening to Uyghurs is important because that technology exists and it is going to happen to you if you do not watch it. And that I think has worked. The first stage is for the audience to kind of see something, be shocked or afraid or emotionally affected or cry or whatever and then understand something new and then think I have to do something myself and not just wait for everyone else.

Definitely not wait for the politicians to come and save us, right? And also not just say, well, go and vote. Because I do not feel that right now. Terrible as it is to say, I do not feel the answer would have been had I voted this way everything could be great. Well, I do not think so. And I think that is where there is a bigger system shift that needs to happen. And so that is only going to happen if we do bigger things. We have got to change laws, we are going to protect ourselves in different ways and fight for our rights which are being eroded every single day.

But as well as that, we can start off by deleting a few apps and we stop using certain things that are making them richer. Looking at what our kids are watching, looking at what your mum understands, looking at what your friends are saying and holding them up and saying you should not say that. You know, where have you got that information? I think there is a kind of macro and micro level at which we have to do something.

And so far the people that have seen the film, most people I have communicated with or who have reacted to the film, have been affected by it and have done something to change something. And if we all do little things, then maybe we can do big things in the grand scheme.

The extract was slightly edited for clarity and brevity.